An unconventional group occupied the yellow Georgian carriage, their faces paunch, their breath unclean, but their clothes were the finest money could buy, and the gaze on all of them was glowing with the effects of copious amounts of the mother’s ruin. Heated talk hid concern about revolution and the under-class. Nevertheless the bumpiness of the carriage with the crest of the King stamped on the doors brought hush to proceedings.

Time passed randomly, like disobedient criminals being herded into a slum prison. Then the Georgian lot belched their opulent lunches over each other without manners—while the hard wheels on the carriage skidded over the cobbled streets and the turds grooved into the cracks like squashy cement.

A misty fog appeared; it seemed similar to an apparition, a ghost, which had found a way to manifest from the ‘The City of the Dead’. The carriage rushed through the fog and along a muddied puddle; it reflected a sullen bleakness in the swirling water amongst the dead flies, autumn leaves and crushed beetles.

Nearby, blind men begged. Shoeshine boys played with stones. Street urchins joked. Shoeless children cried—cold and hungry—wanting nothing more than a warm place of solace. Women of the night, crimson dressed came onto the scene; noticing the rich types in the carriage were former punters.

Crippled soldiers from The Battle of Waterloo ‘bemoaned’ their woes and anguish, as they hobbled beside each other, one without an eye, one without a leg, and two without an arm. All these soldiers’ eyes held a story of despair within them, mainly of the futility of war. Tears followed, carrying parts of their soul, parts of their dignity, and the remnants of what faith they had left.

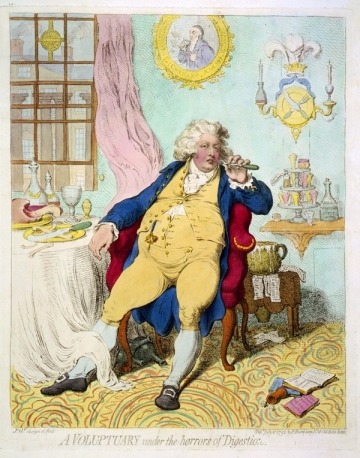

The aristocratic Georgian Society in the carriage mirrored the Prince Regent’s glut perfectly. A man so consumed with debauchery, that he was the butt of many cartoonists’ mockery. Even his own father, George III, thought his son was nothing more than a tree, growing sea green apples in an orchard somewhere in the Kent countryside. The King truly was…Mad as a March hare.

The carriage drew to an abrupt halt. The horses neighed, raising their hooves into the sky. They coughed. Snorted, and their bits were covered in frothy foam. Then they defecated onto the streets. The steam from their relief carried an offensive stench thick with unpleasantness. A street urchin hovering in the wings held his nose.

‘Cor! What a stink.’ He moved closer, his expression ambitious and bold. He saw a chance, and sprang up against the carriage door, peering through the window opening.

‘Penny guvnor. Penny for poor old me. I sleep in the shadows. Not wanting anything more, than a cup of warm gruel, and a bed in the doss house.’

The white wigged Georgian man in the carriage frowned with disdain, lips pallid, eyes contemptuous. He raised his white-gloved hand, beckoned the boy forwards, then swiftly slapped him around the face causing his ears to pop.

‘Be gone urchin!’ snapped the Georgian man. ‘Rabble-rouser and scallywag! Writhe in the mud with your own class.’

The boy was furious; he drew all his strength from this abuse, darted back to the carriage window and spat mucus into the face of his abuser. A brief silence brought a moment of solidity. Bang! A pistol shot fired into the face of the boy. Killing him instantly. A commotion occurred in the street nearby. Rough types darted onto the scene, their human frames expanding in the hoary nightlight. Then the loud crack of a whip caused animal’s shrieks to turn into a raucous pant. The horses reacted and the carriage pulled away, leaving the ugly crowd behind to fight and remonstrate amongst themselves. Georgian Society was certainly an unforgiving place, if you were poor, destitute, and living on the mean streets of London.